(2)_1608056647.png)

(2)_1608056647.png)

Зельма Меербаўм маладая паэтка з Чарнаўцоў, якая стала вядомай ва ўсёй Еўропе толькі праз дзесяцігоддзі пасля сваёй трагічнай смерці ад знясілення і хвароб у нацысцкім лагеры. Яе вершы, якія захаваліся да нашых дзён, працягваюць уражваць чытачоў сваёй шчырасцю і з’яўляюцца пераканаўчым сведчаннем яе выключнага паэтычнага таленту. Чулае сэрца дзяўчынкі перадае смутак і боль, якія давялося перажыць яўрэям Чарнаўцоў падчас Другой сусветнай вайны.

Я хочу жити.

Глянь, який барвистий світ!

В нім стільки є м'ячів і гарних плать.

І стільки уст чекають і горять,

Щоб пити щастя юних літ.

Зельма Меербаўм, «Верш» (07.07.1941)

[Пераклад Пятра Рыхло]

Дзяцінства

Зельма нарадзілася 5 лютага 1924 года ў сям’і дробнага гандляра Хаіма Меера Меербаўма і Фрэдэрыке Шрагер. Калі дзяўчынцы было ўсяго 9 месяцаў, яе бацька захварэў і памёр. Пазней яе маці пабралася шлюбам другі раз – з Леа Айзінгерам. Айчым Зельмы працаваў простым ткачом, і таму сям`я магла сабе дазволіць толькі невялікую кватэру на вуліцы Біларгас, нумар 38. Аднак дзяўчынка шмат часу праводзіла ў хаце сваёй бабулі, якая была яе самым лепшым сябрам.

Маладосць

Зельма расла вельмі актыўнай, а часам нават няўрымслівай дзяўчынай. Вучоба ніколі не вабіла яе. Асабліва, калі пасля ўсеагульнай румынізацыі школьнай адукацыі прыватная нямецкамоўная школа для дзяўчынак Хофмана на былой Альтштрасе была пераўтворана ў Liceul Particular de Fete cu drept de publicitate. Тут было створана непрыязнае асяроддзе для яўрэйскіх вучняў, характэрнае для румынскіх школ таго часу. Тым не менш, дзяўчынка даволі добра вучылася па некаторых прадметах (напрыклад, нямецкай мове і літаратуры, рэлігіі). Зельма шмат і з вялікай асалодай чытала. Яе любімымі аўтарамі былі Генрых Гейне, Райнер Марыя Рыльке, Поль Верлен, Рабіндранат Тагор і іншыя.

Зельма была таварыскай асобай, яна любіла бавіць час на свежым паветры са сваімі аднакласнікамі і лепшымі сябрамі – Эльзе Кэрэн і Рэне Міхаэлі. Таму нядзіўна, што пазней яна зблізілася з членамі сіянісцкай моладзевай групы «Hashomer Hatzair» (Хашомер Хацаір). Аднак, здаецца, яе цікавіла не столькі ідэалогія, колькі сяброўская кампанія. Менавіта ў «Hashomer Hatzair» яна сустрэла Лейзера Фішмана, яўрэйскага хлопчыка, які стаў яе першым і апошнім каханнем. Выглядае на тое, што Лейзер не ведаў ці зрабіў выгляд, што не ведае аб пачуццях Зельмы. Дзяўчына не адважылася падзяліцца імі і замест гэтага перанесла свае эмоцыі ў паэтычныя радкі. Свой першы верш яна напісала, калі ёй было пятнаццаць гадоў.

Калі Зельма заканчвала школу, у Еўропе распальвалася полымя Другой сусветнай вайны. Трывожныя прадчуванні, якія ўзмацняліся з кожным днём, паклалі канец бесклапотнай маладосці Зельмы і яе сучаснікаў.

Гета ў Чарнаўцах

і дэпартацыя

З прыходам у горад 5 ліпеня 1941 г. румынскіх і нямецкіх войскаў, у яўрэйскім квартале пачаліся пагромы і забойствы. На шчасце, дом Айзенгераў знаходзіўся далёка ад цэнтра пагрому, і таму першы акт драмы пад назвай «ачыстка горада» ад яўрэяў не закрануў Зельму і яе сям’ю. Аднак неўзабаве трагедыя ўступіла ў новую фазу. У кастрычніку па загадзе румынскай адміністрацыі ўсе яўрэі павінны былі перасяліцца ў гета. Зельме і яе бацькам зноў пашанцавала: кватэра яе бабулі знаходзілася на тэрыторыі гета, таму ім не давялося шукаць прытулак у дамах незнаёмых людзей, альбо, як і многім іншым, пакутаваць халоднымі восеньскімі начамі на гарышчах, у паграбах і пад.

Неўзабаве іх чакалі новыя рэпрэсіі – дэпартацыі ў Трансністрыю, як румыны называлі тэрыторыю на ўсход ад ракі Днестр, куды прымусова вывозілі ўсіх яўрэяў. Айзінгерам пашанцавала ў трэці раз: айчым Леа, меў, як гэта акрэслівалася ў той час «карысную» прафесію, таму ён атрымаў дазвол для сям’і застацца ў Чарнаўцах. Гэта дало магчымасць Зельме пазбегнуць лёсу сваіх шматлікіх сяброў, для якіх наступная зіма стала апошняй. Дзяўчына даведаецца пра гэта пазней, калі яе саму вышлюць у Трансністрыю. Пакуль яна толькі ведала, што яе каханы Лейзер едзе ў працоўны лагер у Румыніі. Зельме хацела, каб ён узяў з сабой яе альбом, але Лейзер не прыйшоў развітацца.

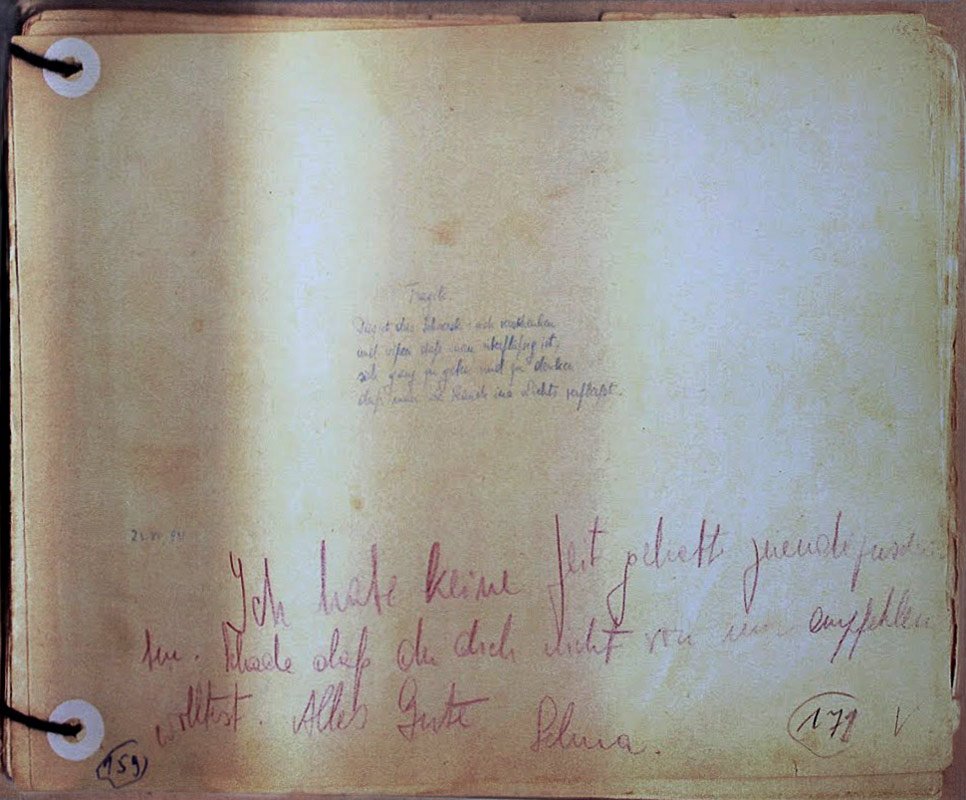

Праз некалькі месяцаў Зельме самой давялося пакінуць родны горад. Айзенгеры не змаглі пазбегнуць другой хвалі дэпартацыі. 28 чэрвеня 1942 г. яна ў таварным вагоне адправілася на ўсход. Перш чым яна прыехала на месца збору, якое было арганізавана на стадыёне таварыства Макабі, дзяўчына паспела перадаць сяброўцы свой найвялікшы скарб – альбом з 57ю вершамі і просьбай перадаць іх аднойчы Лейзеру.

Пазней яе чакала Трансністрыя, гранітны кар’ер на правым беразе Паўднёвага Буга недалёка ад Ладыжына, зноў гета і салдаты СС, якія шукалі рабочых для будаўніцтва стратэгічнай дарогі каля горада Гайсін. Ёй даводзілася працаваць у спякоту, дождж і снег, заставацца ў месцах, якія не былі прызначаныя для жыцця. За некалькі месяцаў голад, холад і цяжкая праца знясілілі маладую дзяўчыну, якая была безабаронная перад тыфам. Шанцаў выжыць было мала. Хвароба перамагла 16 снежня 1942 года.

Жыццё ў слове

Памяць пра вясёлую чарнавіцкую дзяўчыну Зельму пражыла б не даўжэй, чым пакаленне тых жыхароў Чарнаўцоў, якія ведалі яе асабіста. Але дзякуючы вершаванаму альбому, які трапіў да яе лепшай сяброўкі, яе імя захавалася ў гісторыі. Здаецца, Лейзер прадбачыў праблемы, з якімі ён можа сутыкнуцца, і не адважыўся ўзяць яго з сабой падчас свайго непрадказальнага падарожжа ў Палестыну. Ён аддаў альбом блізкаму сябру Зельмы Рэнэ Міхаэлі. Лейзеру Фішману не было наканавана дабрацца да зямлі абетаванай. Рэне, аднак, усё ж такі ўдалося гэта зрабіць. Вось так былі захаваны вершы Зельмы, якія нарэшце трапілі ў Ізраіль. У 1976 г. яны былі ўпершыню апублікаваны былым настаўнікам Зельмы Гершам Сягалам.

Сёння вершы Зельмы добра вядомыя. Яны натхняюць мастакоў многіх краін на стварэнне твораў мастацтва, музыкі, тэатральных п’ес і спектакляў. Вершы «Букавінскай Ганны Франк» перакладзены на многія мовы. Украінамоўныя чытачы могуць атрымліваць асалоду ад іх дзякуючы перакладам Пятра Рыхло, прафесара Чарнавіцкага нацыянальнага ўніверсітэта імя Юрыя Федзькавіча.

Пятрў Рыхло – украинські літаратуразнаўца, педагог, перакладчык. Менавіта ён пераклаў вершы Зельма, якія пазней увайшлі ў зборнік «Я тугою агорнута ...»

Лірыка Зэльмы вельмі інтымная, і сама Зэльма не думала пра тое, каб праславіцца гэтымі вершамі. Гэта быў яе асабісты інтымны літаратурны дзённік у паэтычнай форме, і менавіта гэтая наіўнасць, безабароннасць у душы захапляе ў яе вершах, таму, калі я пераклаў цыкл яе вершаў, якія былі надрукаваныя ў розных чарнавіцкіх газетах, узнікла ідэя аб’яднаць гэтыя вершы, каб завершыць гэтае выданне ў выглядзе кнігі. Прыезд знакамітай нямецкай актрысы Ірыс Бербен, якая чытала вершы Зэльмы на нямецкай мове ў Яўрэйскім доме, адыграў тут важную ролю, і я чытаў пераклады на ўкраінскую мову. Гэта быў вельмі пранізлівы, шчымлівы вечар, і пасля гэтага стала зразумела, што гэтыя вершы трэба данесці да ўкраінскай чытацкай аўдыторыі, бо такі скарб не павінен застацца незаўважаным. Такім чынам, я неўзабаве скончыў гэтую кнігу і пераклаў усе вершы.

Прагледзіць тэкставы варыянт