У пошуках гета

Як мы адкрылі невядомыя

старонкі гісторыі Чарнаўцоў

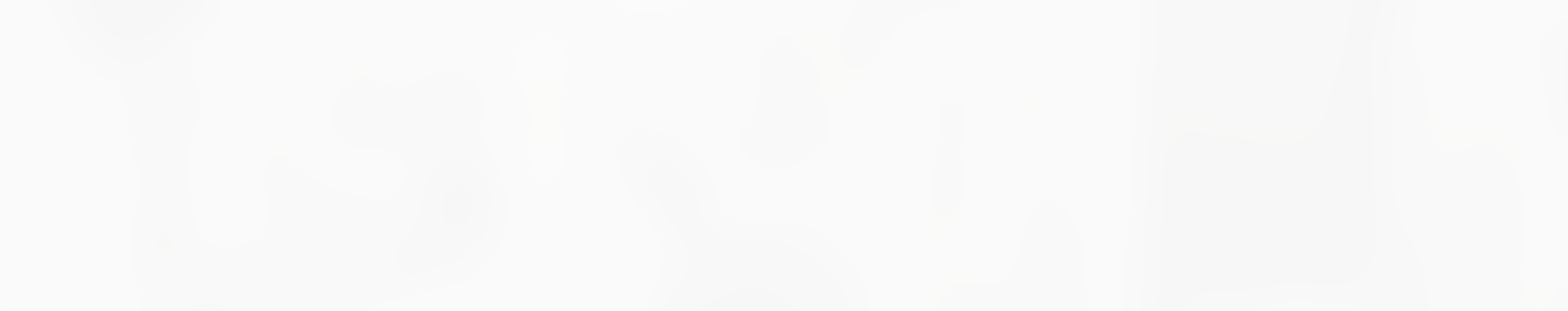

У пачатку кастрычніка 2020 года ў рамках міжнароднага адукацыйнага дыджытал праекта «Вымяраючы гета: Гродна – Чарнаўцы – Кішынёў» нам – двум старшакласнікам Чарнавіцкай гімназіі №1 імя Тараса Шаўчэнкі і студэнту Чарнавіцкага нацыянальнага ўніверсітэта імя Юрыя Федзькавіча – было дадзена заданне расказаць гісторыі нашым равеснікам у двух іншых горада-партнёрах па праекце – Гродна, Беларусь і сталіца Рэспублікі Малдова – Кішынёў, гісторыю Чарнавіцкага гета ў 1941 годзе.

Ніхто з нас не меў дастатковай гістарычнай фактуры. Таму, спачатку мы павінны былі самі адкрыць для сябе гэтую гісторыю. Мы раздзялілі задачы паміж сабой: аналіз даступнай інфармацыі па тэме ў Інтэрнэце і ў школьных падручніках, пошук матэрыялаў у мясцовых бібліятэках і архівах, а таксама апытанні мясцовых экспертаў, якія маглі б нас пракансультаваць. У нас быў усяго месяц на ўсё, і мы не ўяўлялі, як гэта рэалізаваць.

Пошук неабходнай інфармацыі ў школьным падручніку за 10-й класа не прынес патрэбных вынікаў. Адзінае месца, дзе згадваліся падзеі патрэбных нам гадоў, быў пункт «Украіна ў гады Другой сусветнай вайны». На старонцы 205 мы знайшлі згадку пра Халакост ва Украіне, але пра падзеі ў нашым горадзе не было ні слова, не кажучы ўжо пра гета.

Пошук у Інтэрнэце быў больш эфектыўным. Першапачаткова ключавыя словы «Халакост ва Украіне» вывялі нас на афіцыйныя сайты двух музеяў – «Памяць яўрэйскага народа і Халакост ва Украіне» ў Дняпры, і Мемарыяльны цэнтр Халакосту «Бабін Яр» у Кіеве, але ні ў адным з іх звестак пра Чарнавіцкае гета не было. Пасля змены крытэрыяў пошуку (у першую чаргу мовы) мы нарэшце знайшлі некалькі вельмі цікавых сайтаў:

- Афіцыйны сайт нацыянальнага мемарыяла ЯдВашэм Ізраіль у Іерусаліме.

- Афіцыйны сайт Мемарыяльнага цэнтра і музея Халакоста ў Вашынгтоне (ЗША).

- Інтэрнэт-платформа міжнароднай віртуальнай супольнасці былых Чарнавіцкай яўрэяў Czernowitz-L Discussion Group.

На названых сайтах мы знайшлі нямала цікавай інфармацыі пра Букавіну і Чарнаўцы часоў Другой сусветнай вайны, у прыватнасці гістарычныя фатаграфіі, дакументы з асабістых калекцый былых жыхароў нашага горада, успаміны, а таксама карту горада з пазначанымі межамі яўрэйскага гета ў Чарнаўцах.

Наступны этап нашай працы над праектам заключаўся ў пошуку матэрыялаў пра Чарнавіцкае гета ў мясцовых бібліятэках і архівах. Перш за ўсё, нас цікавіла, ці захаваліся мясцовыя перыядычныя выданні з 1941 г. да нашых дзён, і калі так, ці асвятлялі яны праблему гета. У выніку доўгіх пошукаў у фондах Навуковай бібліятэкі Чарнавіцкага нацыянальнага ўніверсітэта імя Юрыя Федзькавіча мы знайшлі падшыўку газеты «Буковіна» за 1941 год на румынскай мове, бо ў гэты час Чарнаўцы знаходзіліся пад кантролем румынскіх улад. У нумары за 27 жніўня 1941 г. мы знайшлі артыкул, у назве якога нас зацікавіла слова «Ghettoul». Пошукі перакладчыка з румынскай мовы, а таксама пераклад самога артыкула занялі пэўны час, але ў рэшце рэшт мы пазнаёміліся са зместам паведамлення.

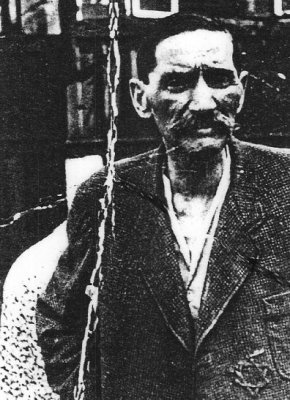

У фондах Муніцыпальнай бібліятэкі імя Анатоля Дабраньскага нашу ўвагу прыцягнулі некалькі выпускаў «Вестніка» – зборніка сведчанняў былых вязняў нацысцкіх лагераў і гета, якія былі выдадзены ў Чарнаўцах на пачатку 1990-х гадоў. Нашай задачай было прачытаць гэтыя сведчанні і выбраць тыя, што былі звязаныя з гета ў Чарнаўцах. Гэтая праца аказалася досыць цікавай. Пакуль мы працавалі над матэрыяламі, супрацоўнікі бібліятэкі параілі нам прачытаць яшчэ адзін зборнік успамінаў, які выйшаў у 1998 г. пад назвай «Калі Чарнаўцы былі яўрэйскім горадам. Успаміны відавочцаў». І ў гэтай кнізе мы знайшлі яшчэ некалькі цікавых успамінаў пра падзеі лета і восені 1941 года ў нашым горадзе.

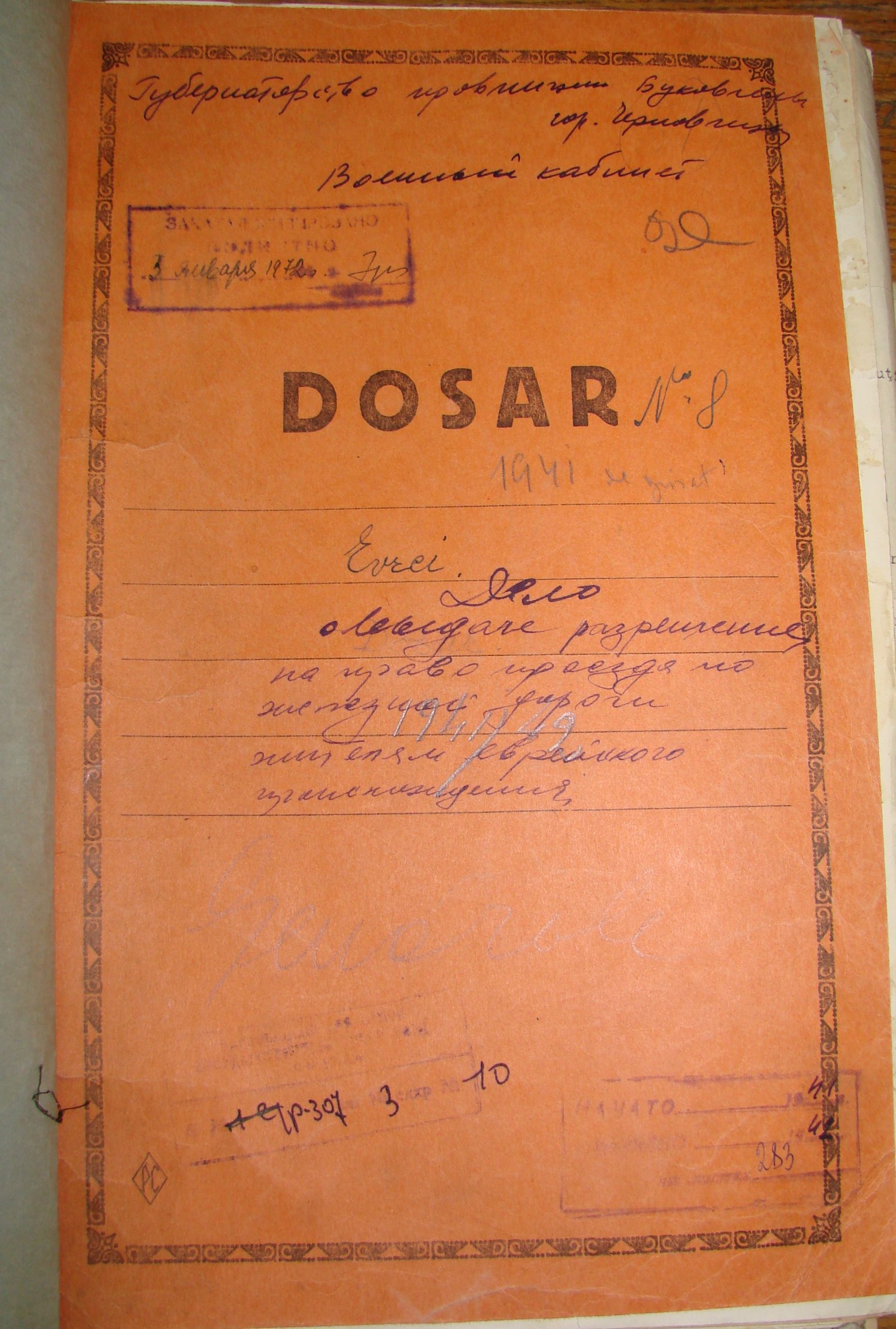

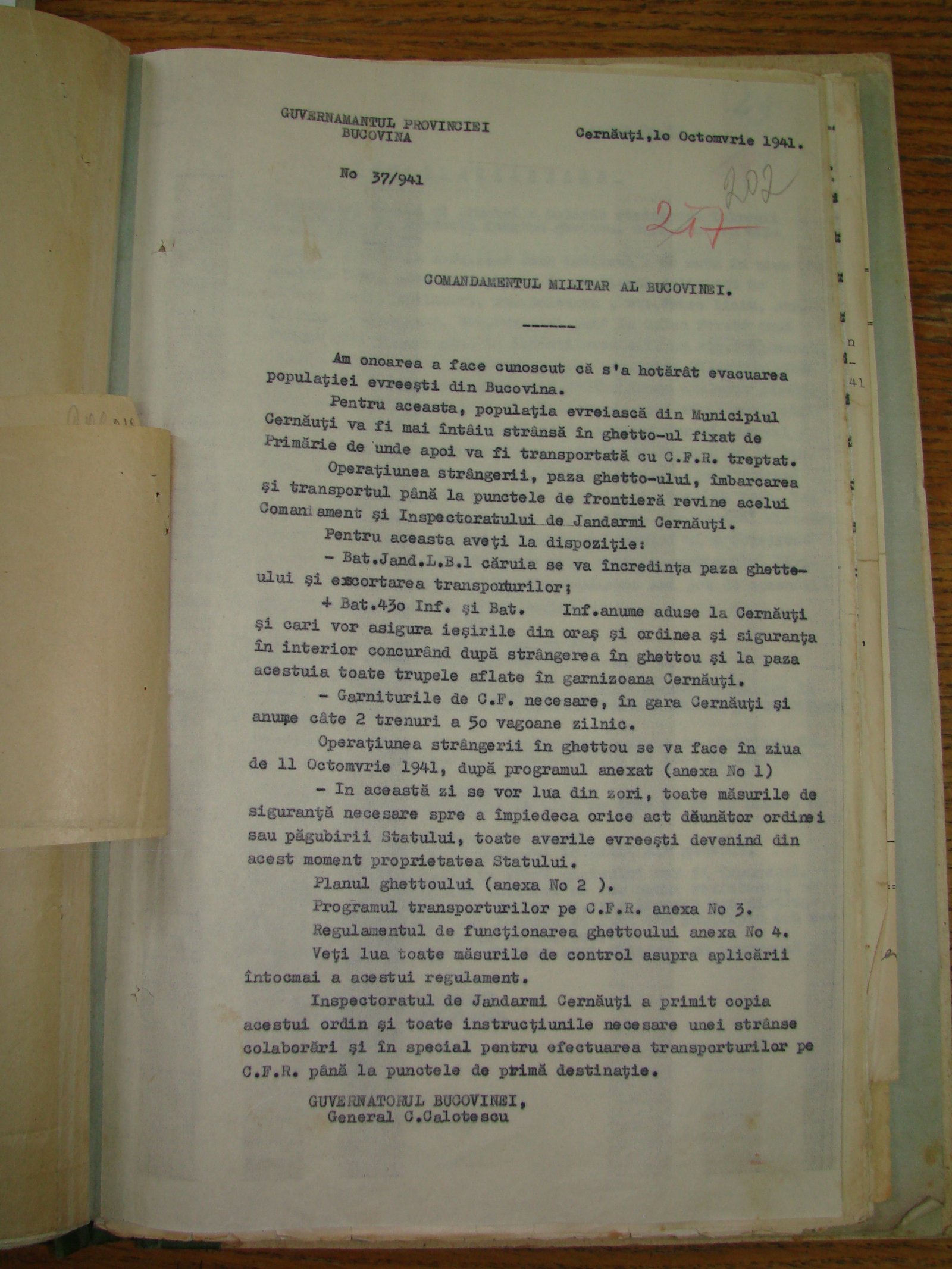

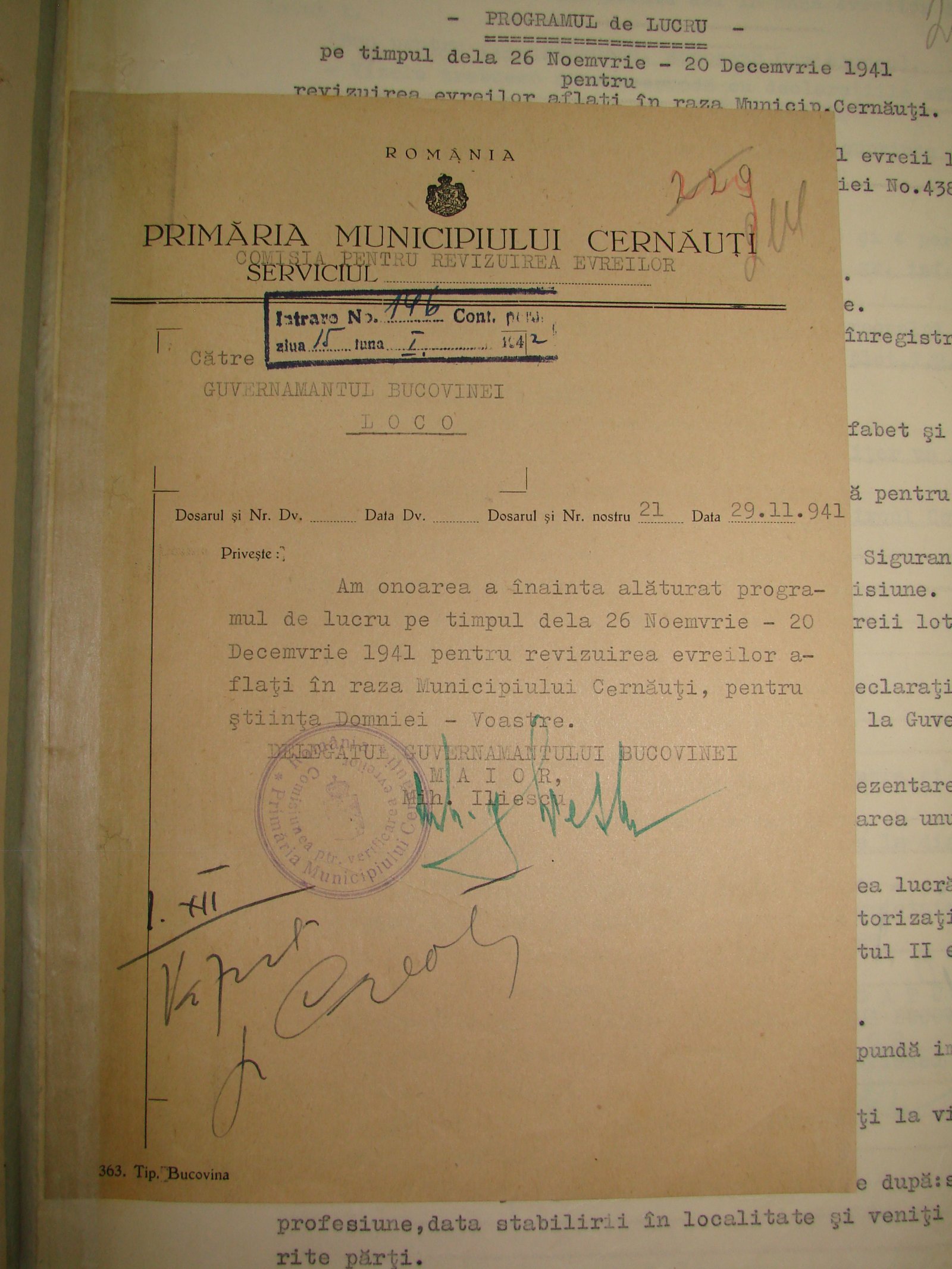

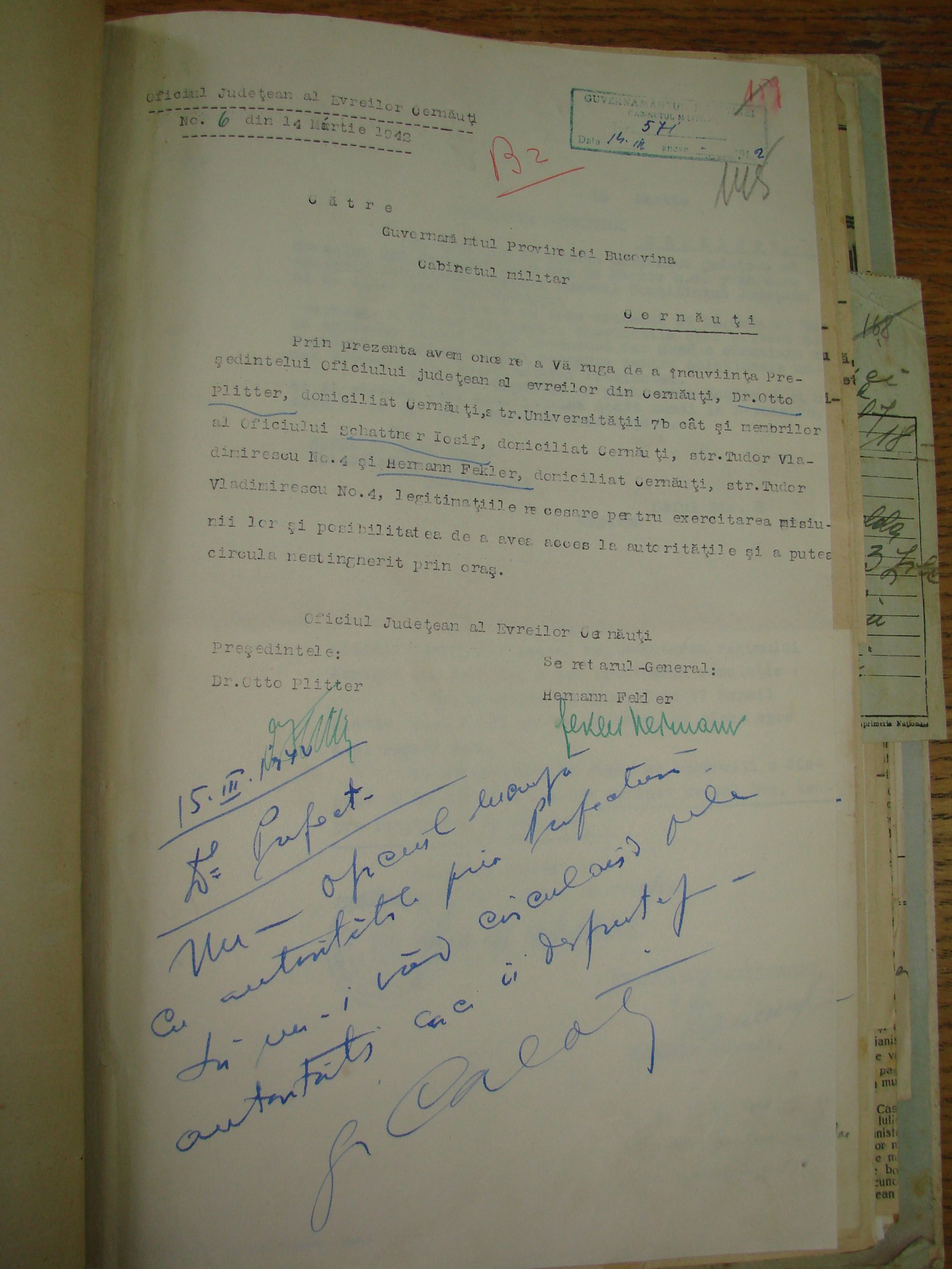

Наступнай месцам нашага пошуку ў рамках праекту быў Дзяржаўны архіў Чарнавіцкай вобласці, дзе мы спадзяваліся знайсці шмат патрэбнай інфармацыі. Нас перапаўняла хваляванне, бо мы не мелі досведу працы з архіўнымі дакументамі. Пошук патрэбнай інфармацыі ў архіўных фондах – дастаткова цяжкі працэс, аднак супрацоўніца архіва ласкава пагадзілася правесці для нас кароткі майстар-клас і дапамагла зрабіць заказ.

Праз некалькі дзён мы прагледзелі пажоўклыя аркушы архіўных дакументаў, якія складаюць невялікую частку вялікага масіва архіву аб Халакосце на Букавіне і ў Чарнаўцах. Большасць дакументаў была на румынскай мове, але супрацоўнікі архіва дапамаглі нам з перакладам. У выніку мы апрацавалі вельмі важныя дакументы, якія непасрэдна тычыліся гета.

Наступнай установай, якую мы наведалі падчас працы над мікрапраектам, стаў Чарнавіцкі музей гісторыі і культуры яўрэяў Букавіны, размешчаны на Тэатральнай плошчы ў будынку былога яўрэйскага народнага дома (цяпер Цэнтральны палац культуры г. Чарнаўцы). Наш гід у музеі быў яго дырэктар, які стаў экспертам у нашым праекце. Ён правёў для нас захапляльную экскурсію па пастаяннай выставе. Тут мы даведаліся пра ўсе асноўныя этапы гісторыі яўрэяў рэгіёна, а таксама зразумелі, чаму тэма Халакоста і гета прадстаўлена на выставе адносна невялікай колькасцю матэрыялу. Каб задаволіць наш інтарэс да гэтай тэмы і дапамагчы нам выканаць заданне, спадар Мікола Кушнір прапанаваў падрабязна расказаць гэтую гісторыю на камеру. Мы з задавальненнем скарысталіся гэтай прапановай. І вось што атрымалася.

Пра асаблівасці Чарнавіцкага гета

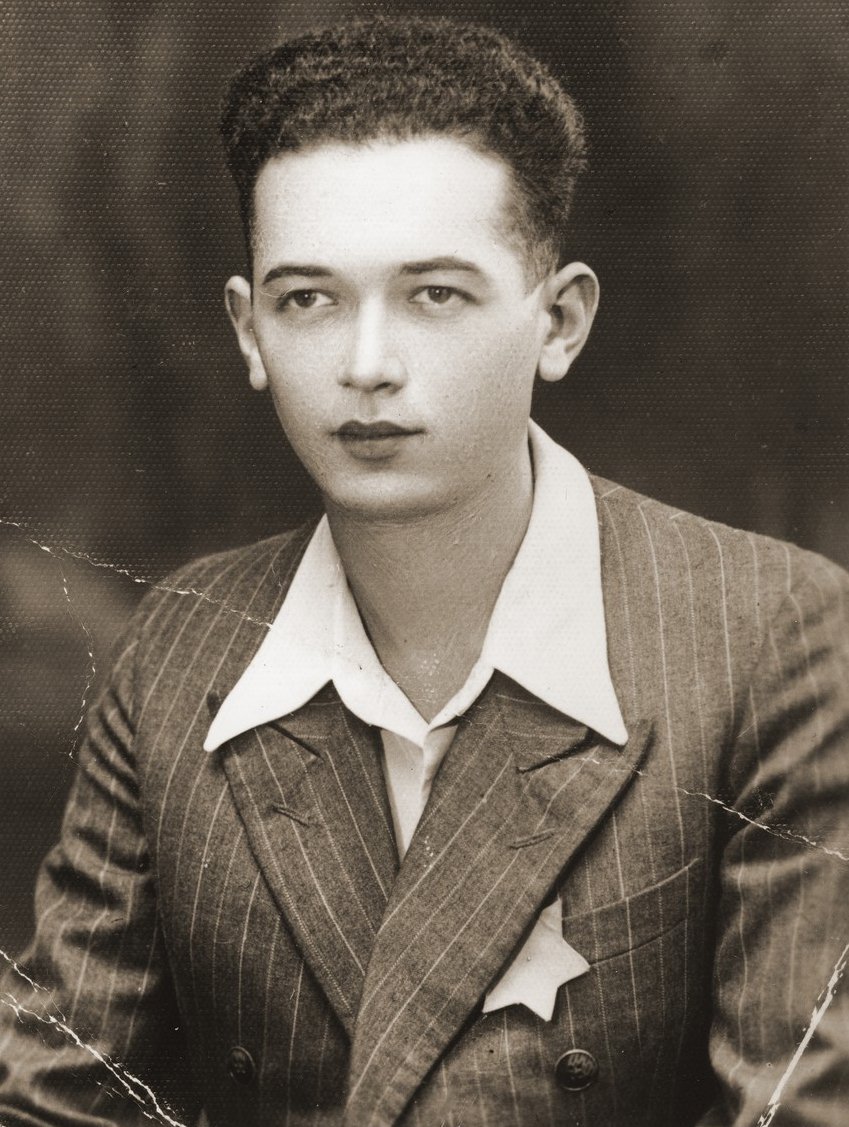

Пра ўмовы знаходжання яўрэяў у чарнавіцкім гета

У ходзе размовы з дырэктарам музея мы даведаліся таксама, што існуюць відэа-ўспаміны непасрэдных сведак Халакоста ў Чарнаўцах, якія на сабе зведалі, што такое гета. Для выкарыстання гэтых успамінаў, калекцыямі якіх валодаюць некалькі міжнародных даследчых цэнтраў, патрабуецца спецыяльны дазвол. Таму ў якасці прыкладу мы прапануем тут невялікі фрагмент, які толькі дазволіць скласці ўяўленне пра гэты від гістарычнай крыніцы.

Каб зразумець падзеі генацыду супраць ярэяў у Чарнаўцах, а таксама ролю гета ў гэтым працэсе, мы пры дапамозе сучасных камп’ютэрных тэхналогій і вопытных спецыялістаў стварылі лінію часу, якая ўзнаўляе храналогію падзей Халакоста ў нашым горадзе.

Цікавай часткай нашай працы над мікра-праектам было наведванне той часткі нашага горада, дзе восенню 1941 года было створана гета для яўрэяў. Мы некалькі дзён хадзілі маленькімі вулачкамі і завулкамі старога горада і даследавалі, дзе менавіта праходзілі межы гета і дзе знаходзіліся асноўныя элементы яго інфраструктуры. Нам спатрэбілася спецыяльная карта, якая была падрыхтавана Чарнавіцкай вучнямі ў рамках школьнага праекту пад кіраўніцтвам настаўніцы гісторыі Чарнавіцкай школы №41 Наталлі Паўлаўны Герасім.

Сляды былога гета цяжка знайсці ў сучасных Чарнаўцах. Пра яго існаванне нагадваюць толькі мемарыяльныя дошкі на старых дамах, а таксама помнікі, пастаўленыя ў розныя гады і ў розных месцах, дзе калісьці знаходзілася гета. Сёння яны выступаюць ахоўнікамі памяці. Стоячы побач з імі, мы зразумелі, што нездарма марнавалі час на пошукі. Таму што для тых, хто ўзброены неабходнымі ведамі, гэтыя дамы, вуліцы і помнікі ўжо не проста маўклівыя сведкі гісторыі. Цяпер яны цікавыя суразмоўцы. Пры нагодзе паспрабуйце і вы паразмаўляць з імі.